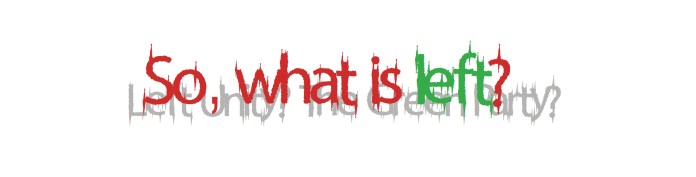

Sean Thompson maps the alternatives to the left of Labour and sees potential in a insurgent and rapidly growing Green Party

Two resolutions to Left Unity’s national conference in November mentioned the Green Party and serve demonstrate the Left’s confusion about what attitude to take to the party’s astonishing growth in membership and polling numbers; one calls for ‘structured collaboration…between serious forces on the left at the 2015 election, including the Green Party’, while the other states that ‘we will not call for a vote for…the middle class Greens’. Clearly, we on the left need to get our act together and decide on the sort of relationship we want to develop with the Green Party. In my view, it is essential that we not only have a realistic understanding of the party’s politics and its support base, but that we develop a positive (but critical) working relationship with them wherever we can.

It’s only a bit more than eighteen months since Ken Loach, appearing on BBC’s Question Time, said that what Britain needed was a ‘UKIP of the Left’ and so kick-started the initiative that was to become Left Unity a few months later. However, since May it has started to look more and more as if it is the Green Party which is beginning to match that description. Membership of the Green Party of England and Wales (GPEW) is booming: it now stands at around 52,000 – and increase of almost three and a half times on their membership figures (15,000) in January last year. Membership of the Young Greens (party members under 30 or full time students) has increased from around 2,000 a year ago to 11,000 or so today. In the week that the TV companies announced that UKIP would be invited to take part in the election debates between the party leaders next May but that the Greens would not be, the party received an incredible 2,000 membership applications and within three weeks an online petition demanding its inclusion in the debates received over 300,000 signatures. Given the very modest size of the radical left and the utter irrelevance of all the old far left sects, the Green Party is increasingly being seen by many as the only viable – or visible – left alternative to Labour.

And there is no point in our trying to deny it – the Green Party is certainly now a party of the left. Caroline Lucas has said on TV that she is proud of the party’s ‘socialist traditions’ and both she and the party’s current leader, Natalie Bennet, have publicly said that they are comfortable with being described as ‘watermelons’ (green on the outside but red on the inside; the epithet thrown at socialists in the party by right-wingers and the title of Green Left’s conference bulletin). There is relatively little in its formal list of policies that any of us would take violent exception to; the party is opposed to Trident and NATO, and in favour of the renationalisation of the railways and public ownership of buses, water, gas and electricity. It is opposed to the privatisation of the NHS and its education policy is all but identical to the NUT’s. It is opposed to current anti-trade union laws and the proposed TTIP and supports the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions campaign against Israel. Oh, and in addition to publicly supporting the People’s Assembly Against Austerity, the party supports CAMRA’s Beer Drinkers and Pub Goers Charter! In other words, most of the time we agree with each other on most things.

However, its politics are syncretic and impressionistic, having developed out of, and still marked to some degree by, a narrow and moralistic environmentalism. The nearest thing it has to a clear statement of political position is its Philosophical Basis document, 3,000 mind numbing words of well meaning flannel. As a result, the party’s politics are to a large degree built on sentiment rather than rigorous analysis, and a tendency to be infatuated by various cure-all political remedies, such as Citizens’ Income, Land Value Tax and ‘Positive Money’ (a watered down version of Social Credit). This is compounded by the fact the the party has a very weak tradition of organised internal debate (apart from its twice yearly conferences) and no tradition at all of political education.

The political strategy of the Green Party is based on the unspoken and unconsidered assumption that politics is virtually entirely about fighting elections and political success is entirely about winning them. Thus the whole structure of the party, such as it is, is organised as a rough approximation of an election machine on the lines the three major parties. In those areas where the party is organised enough, its activities are for the most part confined to promoting the Green Party – fighting elections and in between, preparing for the next one by distributing newsletters/leaflets and canvassing. Its presence on demonstrations and in broad labour movement campaigns is usually largely limited to members of Green Left (the ecosocialist tendency in the party), the Green Party Trade Union Group (GPTU) and increasingly the Young Greens.

The GPEW is no longer just an environmental one trick pony – it is a left reformist party and implicitly (and to a modestly increasing degree, explicitly) anti-capitalist. The trouble is, it has no real analysis of capitalism, the state, or who, where or what are the agencies for change. As a result, it has no overall strategy for how to get from where we are to where we want to be beyond getting an ever increasing number of people to vote the goodies into office rather than the baddies. The problem with this sort of voluntaristic radicalism, based on a personal moral imperative and unreinforced by much in the way of analysis or understanding of class politics, is that when push comes to shove, no matter how principled and progressive you are personally, you do tend to get shoved – as the Greens did (and continue to do) when they ‘took power’ as a minority administration in Brighton.

Nonetheless, the more or less conscious move to the left of much of the party’s membership over the past few years, away from the narrow environmentalist niche politics that were, and to some degree still are, its comfort zone, in combination with the recruitment of large numbers of a younger generation attracted by its increasing emphasis on egalitarianism and social justice, has been extremely positive. The Greens are clearly significantly to the left of Labour. They are, whether they realise it or not (and some of them do, in a muddled sort of way) – or whether we like it or not – part of the broad and inchoate movement that has to be brought together to be the basis of a new mass party of the left that can earn the active support and involvement of millions of working people.

Clearly, the Greens are not that party – actually it has not even occurred to much of the membership that that should even be an ambition. The party’s membership is overwhelmingly middle class (although I suspect not that much more so than most other groups on the left). By and large, the areas in which it has done well: Brighton, Norwich, Bristol, Lancaster and pockets of some of the major cities, have a larger than average percentage of youngish, leftish, well educated middle class inhabitants (eighteen months ago, an internal survey found that 38% of the membership had a post graduate degree). However, the Greens have started to see a very modest increase in support in a few working class areas, particularly in the West Midlands.

The problem is that their niche market – the progressive middle class vote – is highly contested and unstable. At the last General Election a good slice of the Greens’ ‘natural’ supporters went to the Lib Dems. Since then, of course, the Lib Dem vote has collapsed and in the elections in May 2014, many of those who chose it in 2010 because of New Labour’s shameful record in government returned to Labour, which has exercised a hegemony over progressive middle class politics for the best part of a century. What will happen next May is anyone’s guess. At the moment the Green Party is neck and neck with the Lib Dems, with the latest Ashcroft poll showing them at 8% to the Lib Dems’ 7%. Caroline Lucas will, with any luck, retain her seat in Brighton (although the party will be hammered in the council election there) but its chances in its other target seats are rather slimmer than it claims. Their electoral support is very evenly spread so they are likely to pick up a very respectable total number of votes which are unlikely to translate into many, if any, additional seats.

When I was in the Green Party I repeatedly pointed out to my comrades in Green Left that the party, while being many times larger than all the far left sects put together, was just as much a sect as any of them. The Green Party may be an unusual sect, in that it is heterogeneous, left reformist and fairly tolerant, but it is a sect nonetheless. Like other sects it is obsessed with the Full and Correct Programme (in this case its Policies for a Sustainable Society rather than the Transitional Programme of 1938 or the British Road to Socialism) which, if presented to the unenlightened masses for long enough will lead them to recognise their previous shortsightedness. Like other sects it tends to view actual concrete struggles through the distorting prism of its own programmatic priorities – including many programmatic points which are good in themselves of course.

To its credit, it doesn’t share with most far left sects an obsession with the Leninist conception of the party (although, arguably, neither did Lenin) but on the other hand it doesn’t have a class analysis (or much of any kind of analysis) of society and the state. And while it doesn’t have any of the other various laughable programmatic tics and obsessions of the ‘old left’ grouplets it doesn’t need them, as it has plenty of its own.

While it is therefore unlikely that the Green Party, left to its own devices, will break out of its political niche, it has demonstrated that it has considerable potential to grow within it. It is at least five times as large as all the groups on the radical left put together, if not larger. Its youth wing is growing at a rate of knots and is the biggest political grouping on an increasing number of campuses. And thanks to the efforts of Green Left (which now has four members on the party’s national executive, including Trade Union Liaison Officer) and Green Party TU group, it is beginning to have some very slight influence in a number of unions – albeit largely at national level.

It would be a grave mistake to write off the Greens as ‘middle class’ or, regardless of their policies and their involvement in progressive campaigns, tacit supporters of the status quo. Many, particularly younger people, are increasingly seeing them as the only viable organisation to the left of Labour – and in many parts of the country they are. In Australia, the Green Party has effectively filled the space to the left of the right wing Labor Party by default, due to the irrelevance (and tiny size) of all the orthodox groupings of the radical left. That was the situation, too, in Germany for many years – and even now Die Grünen, compromised and discredited though it is, still constitutes a major block to the development of Die Linke. Given the tiny size and marginality of the radical left in Britain, it would be ludicrous for us to dismiss the Greens as irrelevant.

The vast majority of Greens see themselves as left wing and a significant proportion are happy to describe themselves as anti-capitalist, including Caroline Lucas. Many consider themselves socialists, and the fact that many more don’t really know whether they are or not is as much a condemnation of the weakness and sectarianism of the Left as a whole as it is of the poverty of political theory in the Green Party.

I believe that building a mass party to the left of Labour has to involve the Green Party, or at least a large part of its membership, in some way. Rather than reject or ignore them I think that we should attempt to engage with them in practical ways and develop a relationship as critical friends. In May, the Green Party aim to be standing in around 500 seats and in the large majority of those are likely to be fielding the only left of Labour candidates. No doubt some comrades might be able to construct some sort of argument for not supporting them in those contests, but it would be an example of the sort of bone headed sectarianism that has been so typical of the British Left over the past few decades and which has been in large measure responsible for us being so discredited and marginalised now.

If, in the future, we want them not to put up candidates against credible socialist candidates in some areas, or wish to persuade them not to stand against the handful of decent Labour MPs (or Plaid in Wales) – or perhaps, not to stand in the two or three places where TUSC has a chance of a more than derisory vote – then we need to take the initiative in backing them as we did in the North West in the Euro elections, at least in constituencies where there is no other left candidate. There is no chance of us negotiating a national agreement with the Green Party in time for the May elections and its peculiar structure and the naive sectarianism of many of its members would anyway make such an agreement very unlikely, but more importantly there is time for us to start to talk to them at local level and begin to discuss how best to co-operate in practical ways to build the anticapitalist movement that we need that is larger and broader than any existing organisation.

This article is based on one first published on the Left Unity website.